Love is resistance.

It’s inefficient; but effective.

It’s effective only if you believe in it, whole-bodiedly. It requires total commitment for it to work. The landing appears after you jump.

Love can look anemic, limp. What can it do against animals with claws and fangs? Can a rose on a gun barrel stop a bullet?

Love can look like a cop out. “Come on, everyone’s family here.” But that’s not the voice of love but of apathy. Love as unconditional acceptance is not apathy. Though they may look like identical twins, they have wildly differing personalities.

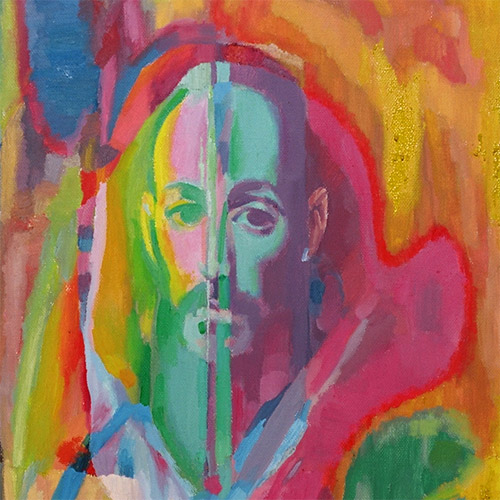

You know that great love poem, invariably read at weddings, pulled out from 1st Corinthians 13? Starts, “If I speak in the tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal,” and ends, “And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.” It’s not for Hallmark cards. Not because it’s too long, but because it’s a declaration of resistance. Because Saint Paul, the birther of this poem, is resistant-par-excellence. Because for Paul, a Christian is a resistant of love.

I know. Christianity looks like a handmaid of conservatism, a lackey of Republicans. That 80% of white evangelicals voted for Trump doesn’t contradict that impression. Jerry Fallwell Jr’s anointing of Trump as America’s messiah was comical and expected. Franklin Graham’s support for Trump’s controversial ban on immigration is so controversial I bet even his father is shaking his head. Nevertheless, they do not reflect the root and soul of Christianity, even if they have the most amped mike. Christianity is not the bulwark of tradition but the stone that shatters it. Jesus, founder of Christianity, said, “Don’t imagine that I came to bring peace to the earth! I came not to bring peace, but a sword. I have come to set a man against his father, a daughter against her mother,” (Matthew 10: 33-34). Christianity is a resistance movement.

Saint Paul was not a rebel, to be sure, but his records prove him a resistant. Look at Paul’s prison record. He was arrested at least twice, once by a mayor and another time by an Emperor. He wasn’t a petty protester serving a night in the local jail. His back got filleted in Philippi, beat in Jerusalem, and shipped to Rome to stand before Nero. If Nero was bothered enough to hear what Paul was saying, then Paul was a resistant. He was ultimately judged a national threat; so much so that the state finally chopped off his head, silencing him, only temporarily. Paul didn’t just challenge an administration but collapsed the foundation of all political systems, their claim to absolute loyalty.

Not that Paul was frenzying his people with smell of freedom then arming them with swords to seize it. Paul was hated by his own people, the Jews, as much as the Romans, maybe even more. His people mobbed him in the Temple and would have murdered him if not for the Roman centurion. The system he threatened protected him; the guards that locked him up served as bodyguards. Thirty Jews swore not to drink a drop of water until they spill the blood of Paul. This conspiracy was exposed and the Roman captain whisked Paul away to another jurisdiction, outside of the prejudiced city of Jerusalem. I wonder if the thirty conspirators kept their promise; probably not.

Paul was a true resistant, not tied to any party, but exposing the lies of every faction. Where was his ground of resistance? If he is only against things, but never for anything, then isn’t he a rebel without a cause?

He wasn’t for anything in this world because everything in this world was relative. This is the vantage of saints, that they are not wholly invested in this world. The world is passing away. His point was not overthrowing the Empire or the Temple, but relativizing them.

Relativizing is the great threat. Empires, be it political or religion, speak in absolutes. They can’t live as seconds.

Ironic. In our post-modern world, where it is fashionable to say all truth is relative, we speak in absolutes. Remember the campaign speeches? Reading the slogans of protesters? Listening to Trump’s rants? And the warnings against Trump’s despotism? Powers prop themselves up in absolutes. Good and evil is the tree we reach for when we need to justify why we must stay in power, or why we must replace power. The authority and the revolutionists, both are absolutists.

Good people do good. Evil policies can only come from evil people. This is how the game is played in democracy, or at least how it has come to be played in American democracy. We are no longer persuading people but rousing the base. Get the people who think like you to vote, and how can you get them to pick up their sofa-gravitating rumps? Make them believe that the opposition is evil threatening all of civilization.

So Mr. Trump colors immigrants as dangerous. His ban has support because there are those who see every Muslim as ISIS, bent on imposing Sharia law in America. But ISIS kills more Muslims because, well, more Muslims resist ISIS. But that type of complexity doesn’t get votes.

And those who resist Trump? Well, there is no question that those who resist are righteous. Trump is Voldemort or Hitler, you choose the genre, movie or history, but you see the resemblance, don’t you, that thirst for power? If you are not against Trump then you are as evil as Trump. A human person by selfishness can do incredibly evil things, but no one is a demon. No one practices an evil laugh before the mirror before donning his suit and tie.

Paul was against everything absolute. He was the first true relativist. He believed absolutisms was demonization. It gave temporal things immortality. If what should die doesn’t die, it is a monster. And this carried to his ethics.

In his letter to Corinth, St. Paul was dealing with a church that was divorcing over whether to eat food sacrifice to idols. This argument sounds quaint to our modern ears as much as our hot topics will be cold to the next generation. But in 1st century A.D. where the Jewish identity was in life-support, it was a life and death issue. The Maccabean revolution started when Matthias killed a Hellenistic Jewish priest who was ready to “compromise” and sacrifice a pig in the temple. It was a politics of identity.

Paul looks at the politicized issue of sacrificed-meat from a different horizon. Look, there is no such thing as an idol. Paul is liberal! But you should abstain from eating anyways because your brother’s faith is important and you don’t want to stumble them. Paul is a conservative!

No. Paul is both and neither. Paul is not stuck in the conservative vs liberal ethics – or rhetoric. His ethic is relative. Because there is a core, a center, another absolute. That is love. Love is absolute.

For Paul, It is Christ’s love proven on the cross. The cross basically disarmed every weapon of every power system. It dismantled their justification that “they” are absolutely right and good. Both Romans and Jews, believed they had the moral right, both politically and religiously, to crucify Jesus. Jesus was evil, the rebel, the blasphemer, destroyer of Roman and Mosaic law. But they were proven wrong. Their judgment was proven wrong because the one damned was justified by God when God raised him from the dead. Whether one believes it or not, Paul believed it and that narrative relativized all powers.

Not only does Christ relativize all absolutes, offering an embodied philosophy on which to resist all claims of absolutes; Christ also models how to resist. Not only the philosophy but the practice of resistance. Christ prays for the forgiveness of his executioners, turns his arms outstretched to be nailed into the open embrace of love. Christ taught his disciples to “love your enemies,” then he went and did exactly did, praying for the forgiveness of his enemies with his depleting breath.

How do you resist? Love them. Your resistance is acceptance, not of their actions but of their life. Turn the other cheek is not submission. It is Rocky Balboa getting back up against Ivan Drago and taunting, “Is that all you got?” tiring your enemy out of their hatred until they see the stupidity of their hatred.

The letter to Corinth is Paul trying to woo back the factions in the Corinth church. Paul is a gifted logician. He can argue like a Roman lawyer and a Jewish rabbi, quote Zeno and Moses in a single sentence. And he does, at the start of his letter. But when he builds up to the culmination of his argument, that of love, he becomes a poet. Love can’t be contained in logical grammar. It is pointed to by metaphors and music, that mysterious transcendence of poetry.

Love does not rejoice about injustice

but rejoices whenever the truth wins out.

Love never gives up, never loses faith,

is always hopeful, and endures through every circumstance.

(1 Cor 13:6-7)

The resistance of the black church in civil rights movement was not political but love. Of course, it was shrewd like a snake, knew that cultural shift requires changes of laws, and that unjust laws must be challenged one local law at a time. But it was innocent as dove, or as innocent as it can be. The commitment to non-violence was its commitment to the innocence of love. Non-violence was both pragmatic and ideal, a resistance of love, the most effective resistant.

Martin Luther King Jr. A saint. A resistant. He waxed poetic about love as a resistance in his own black-preacher cadence:

I’ve seen too much hate to want to hate, myself, and every time I see it, I say to myself, hate is too great a burden to bear. Somehow we must be able to stand up against our most bitter opponents and say:”We shall match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering. We will meet your physical force with soul force. Do to us what you will and we will still love you. We cannot in all good conscience obey your unjust laws and abide by the unjust system, because non-cooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good, so throw us in jail and we will still love you. Bomb our homes and threaten our children, and, as difficult as it is, we will still love you. Send your hooded perpetrators of violence into our communities at the midnight hour and drag us out on some wayside road and leave us half-dead as you beat us, and we will still love you. Send your propaganda agents around the country and make it appear that we are not fit, culturally and otherwise, for integration, but we’ll still love you. But be assured that we’ll wear you down by our capacity to suffer, and one day we will win our freedom. We will not only win freedom for ourselves; we will appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory.